The Dream Mine

by Peter

According to written family history, my third great-granduncle, Daniel Ross Junior, spent some time prospecting in California during the Gold Rush with his brother Alexander. After several unsuccessful months, Daniel had a dream where he saw a certain pattern of hills and a pool of water. He convinced his brother to search for the pool and eventually found it. With some effort, the young men mined $20,000 in gold from the pool (potentially worth some $700,000 today). Returning home to Scotland, they found their family had joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS Church). They also joined the Church and used their wealth to fund the entire family's emigration to Utah.

There is a long history, stretching from ancient times, through medieval Europe, and into 19th-Century America of treasure hunting and mine location through a variety of supernatural means, including local seers, magic mirrors, seer stones, conjuring, alchemy, prayers and incantations, dowsing or witching, and especially dreams. Dreams by religious figures, preadolescent youths, or professional scryers were often used to inform treasure hunters of where to dig and the issues they might encounter in digging.

The figures involved in these supernatural efforts generally saw themselves as beneficial servants of a higher power and rejected association with the powers of darkness. These practitioners existed in parallel to formal established churches and some areas of England had as many or more magic users as clergy.

There is some association between the early days of the LDS Church and this kind of treasure hunting. Joseph Smith, the founding prophet of the Church, was known as a seer in his hometown. This label seems to have come both because of his well-known First Vision in which he saw God and Jesus Christ and from more mundane seership where he helped to locate lost items and the like. He was eventually hired to help a man from southern New York find a supposed lost Spanish treasure, but eventually convinced the man to abandon the attempt.

Under the doctrine of the LDS Church everyone is entitled to personal revelation from God. From the earliest days of the Church, this has led to a tension between individual ideas and institutional control. This tension is typically resolved by constraining the allowable scope of personal revelation: a person may receive revelation for themselves, their family, and any area they've been given responsibility for, but not for any broader scope. Anyone aside from the presiding councils of the Church who presumes to speak for God to the Church as a whole is considered apostate. Over the course of the Church's history, numerous splinter groups have separated from the Church due to their preference for their particular prophet or seer.

Both this tension in personal revelation and the traditional magical arts made their way to Utah with the pioneers. One of the ways that these manifested were through dreams or visions that their recipients claimed pointed the way towards mineral wealth that was often planned to be used for the support of the Church and its eventual prophesied return to Jackson County, Missouri. Over the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, a number of these 'dream mines' were established, including major examples in Santaquin, Alpine, and Brigham City. Jesse Knight, a Provo resident, heard a voice while prospecting in the Tintic Mountains near Eureka. He took this as a sign to start a mine on the spot. A friend, examining the area, proclaimed it Humbug as it did not appear promising. Knight persevered, naming the claim the Humbug. After sixteen years of hard labor, Knight's claim paid off and he became one of the wealthiest men in Utah.

One of the most famous examples of this phenomenon is the Koyle Dream Mine (also called the Relief Mine) in Salem. John Hyrum Koyle was the son of early pioneers to Spanish Fork. A part of his childhood was spent in the difficult circumstances of the "Muddy Mission" attempting to settle additional areas of southwestern Utah. After marrying, he settled on a farm in the community of Leland, a few miles southwest of Spanish Fork. Now mostly incorporated into Spanish Fork, Leland was located in the area south of the Spanish Fork River near the present route of I-15.

Koyle's career as a seer seems to have started shortly after his marriage. Wishing for a personal confirmation of the truth of the claims of the LDS Church, he repeatedly prayed for a testimony. That night, he had a dream in which he was shown the location of a missing cow on a distant piece of his property, including the cow having a broken horn. The next day, seeking the cow, he found it in the location specified and with the broken horn he had seen in his dream. Koyle took the fulfillment of his dream to be certain confirmation of his prayer.

Koyle is reported to have continued to have visionary dreams through a mission to the American South and returning home. Upon returning home in 1894, he gave up farming and became a traveling peddler of butter and cheese in the towns of the Tintic Mining District. The most fateful of his dreams came on the night of August 27, 1894. He was visited by a figure dressed in white and radiating intelligence. The figure took him in the spirit and showed him a nearby mountain to the east of his home. When they reached a certain elevation, the earth parted and they passed into the mountain in what appeared to be an excavated mine shaft. The visitor explained the various strata of the rock as they proceeded down the shaft, particularly pointing out a cream-colored ribbon of rock that marked the way Koyle should follow. At several points along the way, turn-offs were indicated that marked areas of rich ore. Eventually, the tunnel reached an area of quartz webbed with leaf gold. It was, as Koyle would say in later years, there like fish ready for the frying pan.

|

| The mill at the Dream Mine. Ben P L, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Beyond this area of rich ore, Koyle's visitor showed him into ancient mine workings created by the Nephites of the Book of Mormon. He was told that they had mined the same deposits, creating nine large rooms which were now filled with quantities of refined gold, artifacts, and other riches. Koyle was shown the way out of the mine along the old Nephite tunnel into Water Canyon to the south, but told that the tunnel was not stable and could no longer be used.

The vision repeated twice more before Koyle was convinced to follow its guidance. Thrice-repeated dreams were a feature of the European seer culture discussed above and an important confirmation of the truthfulness of a vision. On the third occurrence, the visitor (who Koyle identified as the angel Moroni who had visited Joseph Smith and was integral in the story of the translation of the Book of Mormon) told him that neighbors digging a well would strike water at exactly noon the next day. Koyle asked his wife to watch the digging and learned that they did, in fact, strike water at exactly noon.

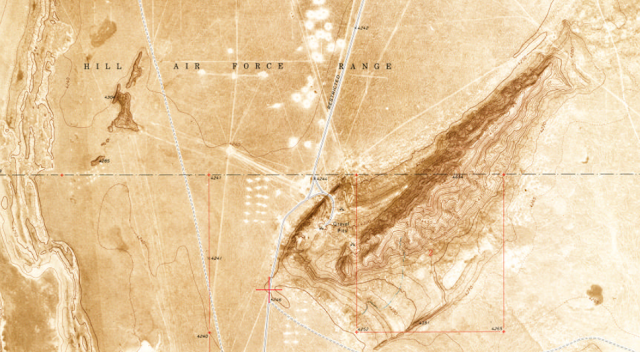

Koyle shared his vision with some of his friends, who likely had heard or had experience with his earlier successes foretelling the future. Koyle took a friend who doubted the veracity of his vision, Joseph Brockbank, to the area identified in his dream. After digging a few feet, they struck a cream-colored rock matching the guiding stratum identified in the vision. Koyle and several friends staked claims on the mountain and commenced sinking a shaft.

As the mine progressed, Koyle's visions of the future of his mine became increasingly grand. The mine would provide funds to feed thousands when the US financial system crashed and paper money became worthless, would provide funds to allow the LDS Church to return to Missouri (part of a last-days prophecy that is part of LDS doctrine), and would build a white city at the foot of the mountain to house 144,000 chosen.

Work on the shaft, presumably following the cream-colored guide rock, was continued by this group of Koyle's family and friends through 1909. After 15 unsuccessful years, the men still involved with the mine recognized the need for additional funds to continue their work. In March 1909, the Koyle Mining Company was incorporated and shares issued to various members. Additional shares were put up for sale to provide funding for further work at a value of $1 per share. Despite having no return on 15 years of work, the shares went quickly when offered with promises, based on additional prophecies by Koyle, of imminent returns of 750 to 1.

With the initial offering snapped up so quickly, the company increased the number of shares for sale and began encouraging purchase in blocks of a minimum of 100 shares (that amount of shares at their projected future valuation of $1,000 per share being enough to sustain a family). People came from around the state to view the workings and some joined in the labor, often being paid in a combination of cash and stock.

By December 1913, the shaft was 1,400 feet deep, so narrow that only two men could work at the bottom, and rapidly filling with water. Pumps struggled to keep the shaft dewatered so that work could continue and the company decided to dig a tunnel that would connect to the bottom of the shaft and allow water to drain at that level. Additional visions and visitations indicated the location for the tunnel.

The increased activity at the mine, along with the promises being made in the sale of stock, brought the Koyle Mining Company to the attention of authorities both secular and spiritual. In particular, the LDS Church began to warn its members against investing in ventures purported to be guided by supernatural means. The Apostle (one of the leaders of the LDS Church) James E. Talmage, a trained geologist, visited the mine in 1913 and observed no evidence that it would ever yield precious metals. With his report, the Church had a statement published in August 1913 that stated in part,

"In secular as well as spiritual affairs, Saints may receive divine guidance and revelations affecting themselves, but this does not convey authority to direct others and is not to be accepted when contrary to Church covenants, doctrines or discipline, or to known facts, demonstrated truths, or good common sense."

A year or so previous to the company offering its initial sale of stock, Koyle had been called as the bishop of the Leland Ward. A bishop is responsible for the operation of a local church unit (called a ward) and for the welfare of the members until his authority. Worried about the mixing of faith and finance in the Dream Mine, the Church released Koyle from his position in August 1913, about three weeks after the official statement quoted above. Followers of Koyle and the Dream Mine still frequently refer to him as Bishop Koyle.

This pressure from the Church resulted in the end of operations at the Dream Mine in July 1914, a shutdown which lasted for six years. However, permission was received to reopen the mine in 1920, as long as it was operated as a normal mining company, with no reference to supernatural means.

The company appears to have frequently announced relatively rich assays of ore, mostly performed by an in-house assayer who was a retired dentist from Arizona. These assays were never confirmed by outside assayers, despite repeated investigations by the University of Utah, Brigham Young University, and commercial assayers. The most prominent of these rich assays occurred in 1929, when they reported finding platinum ore. After the report, the value of stock spiked from $1 or less per share up to $5 or more. The mine was also said to be perpetually on the verge of making rich strikes and theories were invented as to why the assay could not be repeated. The most popular of these was that the valuable metals were going up in 'smoke' during the processing. Several times in the course of its history, the company seized on supposed new methods of refining ore that would allow them to capture the values that they believed were there but were lost in processing. Several inventors were brought to the site to demonstrate their new process, but none were successful. One of the lasting legacies of these efforts is the large, white, building on the mountainside that Koyle had built in the 1930s.

Secular authorities also took note of the mine, particularly its methods for selling stock. The Utah Securities Commission repeatedly investigated the company in the 1920s and 1930s. Several times, despite stonewalling from the Company, the Commission felt it had enough evidence to refer the company and its directors for prosecution, but the Attorney General never felt that the cost of prosecution was outweighed by the potential for success and no action was taken.

The Church repeated its opposition, frequently reprinting the 1913 and other statements, in 1928, 1932, and 1945. This opposition generally coincided with increased activity or excitement at the mine. Eventually, in 1947, Koyle was given a choice to repudiate his claims of divine guidance in respect to the mine and to cease teaching his revelations and selling stock, or to lose his membership in the Church. This was a difficult dilemma for Koyle who appears to have both believed his own revelations and valued his membership in the Church. In the end, he was unwilling to cease teaching his revelations and was excommunicated in 1947. Still convinced that he would imminently strike the rich layer of ore he had foreseen, John Hyrum Koyle died May 17, 1949.

Since Koyle's death, the company was reorganized as the Relief Mine Company, which owns property on the mountain that includes the mine, mill, and several houses. Although there have been occasional announcements that work will restart at the mine, it seems that generally the minimum is done for assessment work to keep the claims valid each year. Taxes are paid based on a gravel mine and orchards using water from the mine tunnel.

Koyle never wrote his own history, stating that he had been instructed in visions not to. This lack can make it difficult to assess his sincerity, as he is reflected primarily in the reports of true believers or convinced skeptics. Although most reports seem to indicate sincerity on the part of Koyle and many of his followers, there are also troubling aspects of affinity fraud schemes in the methods used to sell stock in the company. In any event, the Koyle Dream Mine carries forward ancient beliefs and traditions into the modern-day, providing a fascinating case-study for students of Utah's history.

|

| My terrible photo of the Dream Mine mountain. You can see the mill as a white rectangle in the center of the photo. |

Comments

Post a Comment