Powell Slough: A Case Study in the Differentiation of Federal, State, and Private Lands

by Peter

Some day I'll write a post about the Homestead Act, the Taylor Grazing Act, the development of the Bureau of Land Management, and the Sagebrush Rebellion when western states tried to take back federal land. For now, though, the story of Powell Slough on the shores of Utah Lake offers an interesting history in the development (primarily through the courts) of one aspect of the federal ownership of land.

Powell Slough is an unprepossessing, 700+ acre patch of mud, water, and reeds (phragmites) tucked between an Orem industrial park and Utah Lake. On federal land once used as a fish hatchery, it is now managed as a waterfowl refuge managed by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources under agreement with the Bureau of Land Management. The interesting question, though, is why Powell Slough is considered federal land. It's surrounded by private and state land, and there's no obvious reason for it to be owned by the BLM.

Ownership of a Lake

The roots actually stretch all the way back to English common law, which is the basis for our modern legal system. Under common law, the monarch owned the sea, tidal lands, and navigable waterways. The law evolved this way because running water, much like sunshine and air, were seen as goods that everyone had a right to use, but no one could really own. When the colonies won their independence, each new state took over the role of the monarch and owned their public waters (this was eventually further defined to mean 3 miles from the coast).

Over time, Congress made it customary that new states were created on 'equal footing' with existing states. So, when a territory (such as the Utah Territory) was formed, the government held those public waters in trust for the time when the territory became a state and took ownership.

Now, as you might imagine, the definition of 'navigable' waters is quite open to interpretation. Does it mean someone can rent a canoe and paddle around on the water? Do paying passengers make it navigable, or do you need to be moving freight? A series of court cases reaching to the Supreme Court multiple times established that the water needed to be used for actual navigation at or around the time or statehood. A further series of cases in 1931 (Green, Colorado, and San Juan Rivers), 1971 (Great Salt Lake), and 1987 (Utah Lake) established the navigability and state ownership of various waterways in Utah.

Survey, Settlement, and Resurvey

Not long after the initial Mormon settlement in Utah Valley, federal surveyors began plotting townships and sections and releasing areas for purchase and, later, homesteading. A survey of the Utah Lake shoreline was completed in 1856. At the time, a dam had been built across the mouth of the Jordan River, establishing a relatively high elevation for the water level at the time. Settlers took up land limited by the high water mark. As settlement continued, diversion of water upstream from the lake and compromises on the allowable amount of irrigation water to be stored in the lake reduced the water level, causing the shoreline to recede.

The shore was resurveyed in 1874 and the new areas briefly opened for homesteading. However, the federal government began examining areas for potential use as reservoirs and withdrew the unsettled lands around Utah Lake in 1889. The lake was eventually deemed unsuitable for a large-scale reclamation project because of its significant loss of water to evaporation. The families settled around the lake, particularly in the Powell Slough area, assumed that they owned everything to the shoreline and farmed or ran livestock in the area.

During the 1930s, Powell Slough was used as a fish hatchery.

Legal Resolutions

In 1976, the federal government issued oil and gas leases for the Utah Lake bed. In an interesting reversal of current attitudes, the state sued for ownership of the lake under the equal footing doctrine mentioned above. The United States, while recognizing that states generally owned their navigable waters, claimed ownership of Utah Lake because it had been withdrawn for reclamation purposes in 1889 (see above), before statehood. Although the feds won at the district and circuit levels, the Supreme Court reversed, handing ownership of the lake bed to the state.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the state brought additional court cases against as many as 200 private landowners who claimed land running to the current lakeshore. The courts decided that if private landowners could prove historical title, use, and possession at the time of statehood, they would own the land. In general, they were unable to prove their ownership. The 1889 withdrawal became especially important in this regard, because it established a set of government-owned parcels between private landowners and the lakeshore at the time of statehood.

Powell Slough Today

Today, Powell Slough is managed as a waterfowl refuge by the UDWR. In general, it appears to be primarily used by duck hunters, although birders may visit sometimes, too. It can be difficult to see anything, as the slough is often choked by invasive reeds (phragmites) that can grow to upwards of 10 feet tall, and can cut you up if you aren't careful. The slough also grows some large mosquitoes.

Utah County uses a modified mine sweeper to crush phragmites as part of the fight against invasive species in and around the lake. When I visited Powell Slough last week, it appeared that the area had been treated in the last year or so. You can read about and see a video of the Land Tamer on the Utah Lake Commission Website.

Hotels near Powell Slough can be found in Orem and Provo.

Some day I'll write a post about the Homestead Act, the Taylor Grazing Act, the development of the Bureau of Land Management, and the Sagebrush Rebellion when western states tried to take back federal land. For now, though, the story of Powell Slough on the shores of Utah Lake offers an interesting history in the development (primarily through the courts) of one aspect of the federal ownership of land.

|

| Powell Slough, looking towards Utah Lake. |

Powell Slough is an unprepossessing, 700+ acre patch of mud, water, and reeds (phragmites) tucked between an Orem industrial park and Utah Lake. On federal land once used as a fish hatchery, it is now managed as a waterfowl refuge managed by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources under agreement with the Bureau of Land Management. The interesting question, though, is why Powell Slough is considered federal land. It's surrounded by private and state land, and there's no obvious reason for it to be owned by the BLM.

Ownership of a Lake

The roots actually stretch all the way back to English common law, which is the basis for our modern legal system. Under common law, the monarch owned the sea, tidal lands, and navigable waterways. The law evolved this way because running water, much like sunshine and air, were seen as goods that everyone had a right to use, but no one could really own. When the colonies won their independence, each new state took over the role of the monarch and owned their public waters (this was eventually further defined to mean 3 miles from the coast).

Over time, Congress made it customary that new states were created on 'equal footing' with existing states. So, when a territory (such as the Utah Territory) was formed, the government held those public waters in trust for the time when the territory became a state and took ownership.

|

| Utah Lake. Powell Slough is that green patch on the near shore at the left edge of the photo. This photo was taken from the G Mountain Reservoir. |

Now, as you might imagine, the definition of 'navigable' waters is quite open to interpretation. Does it mean someone can rent a canoe and paddle around on the water? Do paying passengers make it navigable, or do you need to be moving freight? A series of court cases reaching to the Supreme Court multiple times established that the water needed to be used for actual navigation at or around the time or statehood. A further series of cases in 1931 (Green, Colorado, and San Juan Rivers), 1971 (Great Salt Lake), and 1987 (Utah Lake) established the navigability and state ownership of various waterways in Utah.

Survey, Settlement, and Resurvey

Not long after the initial Mormon settlement in Utah Valley, federal surveyors began plotting townships and sections and releasing areas for purchase and, later, homesteading. A survey of the Utah Lake shoreline was completed in 1856. At the time, a dam had been built across the mouth of the Jordan River, establishing a relatively high elevation for the water level at the time. Settlers took up land limited by the high water mark. As settlement continued, diversion of water upstream from the lake and compromises on the allowable amount of irrigation water to be stored in the lake reduced the water level, causing the shoreline to recede.

The shore was resurveyed in 1874 and the new areas briefly opened for homesteading. However, the federal government began examining areas for potential use as reservoirs and withdrew the unsettled lands around Utah Lake in 1889. The lake was eventually deemed unsuitable for a large-scale reclamation project because of its significant loss of water to evaporation. The families settled around the lake, particularly in the Powell Slough area, assumed that they owned everything to the shoreline and farmed or ran livestock in the area.

During the 1930s, Powell Slough was used as a fish hatchery.

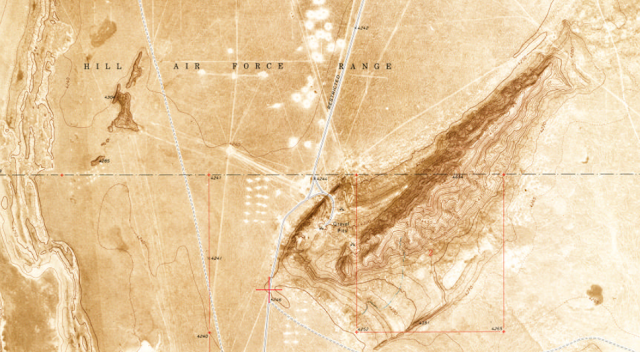

|

| The north entrance to Powell Slough. |

Legal Resolutions

In 1976, the federal government issued oil and gas leases for the Utah Lake bed. In an interesting reversal of current attitudes, the state sued for ownership of the lake under the equal footing doctrine mentioned above. The United States, while recognizing that states generally owned their navigable waters, claimed ownership of Utah Lake because it had been withdrawn for reclamation purposes in 1889 (see above), before statehood. Although the feds won at the district and circuit levels, the Supreme Court reversed, handing ownership of the lake bed to the state.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the state brought additional court cases against as many as 200 private landowners who claimed land running to the current lakeshore. The courts decided that if private landowners could prove historical title, use, and possession at the time of statehood, they would own the land. In general, they were unable to prove their ownership. The 1889 withdrawal became especially important in this regard, because it established a set of government-owned parcels between private landowners and the lakeshore at the time of statehood.

|

| An area of the slough that has been treated for invasive species. |

Powell Slough Today

Today, Powell Slough is managed as a waterfowl refuge by the UDWR. In general, it appears to be primarily used by duck hunters, although birders may visit sometimes, too. It can be difficult to see anything, as the slough is often choked by invasive reeds (phragmites) that can grow to upwards of 10 feet tall, and can cut you up if you aren't careful. The slough also grows some large mosquitoes.

Utah County uses a modified mine sweeper to crush phragmites as part of the fight against invasive species in and around the lake. When I visited Powell Slough last week, it appeared that the area had been treated in the last year or so. You can read about and see a video of the Land Tamer on the Utah Lake Commission Website.

Hotels near Powell Slough can be found in Orem and Provo.

|

| Phragmites in Powell Slough. |

Comments

Post a Comment