by Peter

Note: All photographs in this post are from the National Archives.

On February 5th, 1918 (exactly 100 years ago today), guards at Fort Douglas (adjacent to the University of Utah), discovered a partially completed tunnel from the corner of a barracks building heading in the direction of the perimeter fences. The tunnel had extended perhaps 20 feet of the 45 between the barracks and the outer fence. It was the third such attempt in the month or so that the camp had been open.

|

| Fort Douglas Internment Camp |

This was the enemy alien internment camp at Fort Douglas, Salt Lake City. One of three such camps established in 1918 after US entry into World War I (the other two camps were in Georgia), Fort Douglas held Germans and Austro-Hungarians from across the western United States.

As early as 1914, the War Department began keeping lists of non-citizen Germans and Austro-Hungarians. They particularly focused on those thought to be potential spies or saboteurs and were quite preoccupied with members of the radical labor union Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies). When the US entered the war on April 6, 1917, German ships in US waters were seized and their crews interned.

|

German sailors at work. Note the great sailor hats.

|

Of more concern were the 500,000 non-citizen Germans and 3.5 million non-citizen Austro-Hungarians. Spy hysteria had been building in the country for several years, encouraged by a Woodrow Wilson administration interested in finding pretext for the US to enter the war. All 'enemy aliens,' meaning civilians, were required to register beginning in 1918, and those considered a threat were interned. They were rarely informed of the reason for their arrest, and were jailed indefinitely on the decision of the Department of Justice. Approximately 700 men and eventually a similar number of women registered in Utah. At least 7 were interned, possibly the earliest internees at Fort Douglas on January 5th, 1918.

|

The Utah internees, from the upper left, then left to right. Alfred Frederick Hust, Max Graeske, F.W. Babbel, Erick Pohl, E.H. Fischer, Louis Kessling, Joseph Winkelbaum.

|

Over time, the sailors were moved to other locations, while the number of enemy aliens grew to at least 300, including from Texas, Nebraska, California, and the Pacific Northwest. In general, the men (no women seem to have ever been interned), were treated well.

|

| Some of the writing on the wall names this barracks the "Bloody Bones Hotel." |

Although there were frictions with the guards, they were able to keep gardens, form musical groups and dramatic associations, engage in sporting activities, build model ships, and take classes (in salesmanship, stenography, physiological chemistry, and geology). Many of these activities were sponsored by a branch of the YMCA which opened in the camp. Visits from family members were also allowed and religious services were held. Unfortunately, the lessons and overall restraint of these camps were not remembered when Japanese-Americans were interned three decades later.

|

| The camp orchestra |

|

| Dramatic, indeed |

|

| You have a lot of time on your hands in a prison camp |

|

A marvel of German engineering

|

|

| Leadership is the philosophy of Success! |

A total of 27 men died in the camp. One was a sailor, Stanislaus Lewitski, who fell during a gymnastics exercise at the YMCA and broke his back. The others were all civilian internees, who primarily died of the influenza epidemic that wracked the world in 1918.

Escape attempts continued, with one man cutting his way through the inner fence, but being driven back from the outer fence by a hail of shot from an automatic shotgun in May, 1918. There was no record of a successful escape from Fort Douglas, but three men did escape from one of the Georgia camps. One died along the way, but the other two made it to Mexico and freedom. Camp authorities only became aware of their escape when they sent letters to another prisoner.

|

| Can you see the shotgun? |

The internment camps remained open through 1920, long after the end of the war, as the government decided what to do with the men. Those who wished to return to their native countries were deported, while others were given the chance to return to their lives and citizenship.

Alfred Frederick Hust, shown above and manager of a photography studio, was interned on suspicion of having managed a German spy ring. I imagine nothing was ever proven, because after the war he continued his life in Salt Lake City, with his son attending the University of Utah.

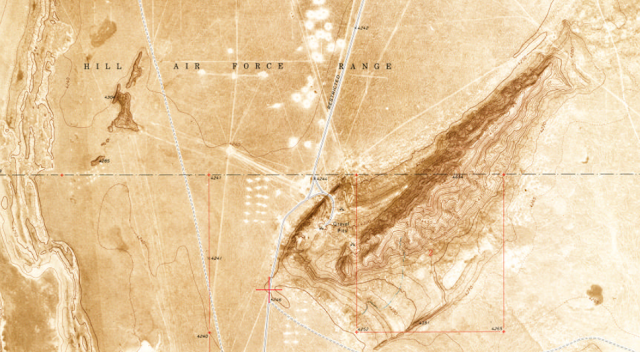

I'm not 100% sure of the location of the internment camp in relation to the current Fort Douglas. I think it may have been west of the current camp, in the area of the basketball stadium, but it could have also been where the student housing currently stands on the eastern portion of the fort.

|

| Commanding officers at the fort. Left to right, Colonel George Byram, the commandant and a retired officer; Major Emery West, the Executive Officer; and Captain AJ MacDonald |

|

| I like this picture because he seems so stereotypically German. This is, presumably, one of the internees. |

For other interesting items in the area, see my posts on the

Salt Lake Army Air Force Jeep Ranges,

Phantom Wye, and

the Longest Conveyor Belt in the World.

Hotels in Salt Lake can be found

here.

I own a picture of an internee named Ernest Verner Evanson [1884-1935] dated Jan 1920 showing the inside of a barracks. Written on the picture "Jan 1920 War Prison Barracks Fort Douglas Utah U.L.A. If you would be interested in adding a scan of this photograph to your article or collection, please write me at carlinotto@gmail.com

ReplyDelete