The Runaway Governor, The Grave Robber, and Fremont Island

by Peter

When pioneers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints first entered the Salt Lake Valley and began to colonize Utah and surrounding areas, the land was part of Mexico. However, following the Mexican-American War the territory, along with California and most of the Southwest, was ceded to the United States.

For seven years, Brigham Young, also prophet and head of the Church, was also the territorial governor. However, in 1858, amid inaccurate reports of the Saints' intent to rebel against the US government President James Buchanan sent troops to enforce obedience and government officials to replace those already in place. There was a crisis, lots of people moved temporarily to Utah County, and eventually a negotiated settlement was reached which led to the establishment of the Army at Camp Floyd in Fairfield and the installation of Alfred Cumming as the second territorial governor. Cumming served for four years, attempting to balance between the hard-line federal judges and the locals. After his term ended, he was replaced by John W. Dawson of Indiana in December 1861.

Dawson's time in Salt Lake City lasted less than three weeks. He reportedly made a pass at a widow. She responded by beating him with a fire shovel. Dawson fled the city on December 31, 1861, possibly to escape the irate relatives of the widow. However, some young men acting as vigilantes caught up to him at Mountain Dell, the first stage stop east of Salt Lake City. They beat him severely and looted his luggage. He returned to Indiana and later gained fame as the first biographer of Johnny Appleseed, his childhood friend. Dawson stands alone as the shortest-tenured governor in Utah history. Which is saying something, as there were several territorial governors during the Ulysses Grant presidency who lasted 3-4 months.

The men who assaulted Dawson were pursued by law enforcement. Of a reported seven assailants, four were arrested and three were killed by police officers while trying to escape.

And then the story gets stranger. But first, a digression into pioneer burial practices. When they first arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, the deceased were interred in what was called Block 49, near the original settlement. This early cemetery was rediscovered in the 1980s during development work and excavated by archaeologists from BYU. These early burials, owing to the poverty of the Saints, were often buried in simple shrouds fastened with brass pins, although coffins were also found.

Some residents, seeking a quieter and more scenic location for their loved ones to rest, began to inter the deceased on a foothill northeast of the city (the Sexton's House is at 4th Avenue and N Street). This was quickly normalized into an official cemetery owned by the city and an ordinance was passed to disallow burial in other locations.

So, Moroni Clawson had been one of the young men arrested for assault. He escaped from the penitentiary, but was shot by a Salt Lake City officer while fleeing. His family did not immediately claim the body, so a member of the police force, Henry Heath, paid for burial clothing out of his own pocket and Moroni was interred in the city cemetery.

A week later, Moroni's brother George exhumed the body to move it to the family plot. He was surprised to find, and Heath was surprised to hear, that there was no clothing at all. Heath began to investigate and hit upon a gravedigger, Jean Baptiste. Baptiste had lived in Salt Lake City with his wife for around three years. When officers visited his home, they found boxes of stolen shoes, clothing, and other goods taken from approximately 300 graves.

The reaction to the crime among the populace was intense. We should remember that the Saints had been driven from every previous place they had lived, leaving behind the graves of parents, siblings, spouses, and children. Not to mention the mostly unmarked graves left along the trail west. The idea of having a place for their dead to rest, where they could watch over them, was important.

A mob gathered outside the jail, threatening to lynch Jean Baptiste. The police department, hoping to keep him safe until trial, smuggled him out of the jail to Antelope Island. They quickly moved him to Fremont Island, which was more inaccessible.

Fremont Island, named after explorer, military officer, and presidential candidate John C. Fremont, had been named by Captain Stansbury during his survey of the Great Salt Lake, although it had also been called Castle Island, Miller's Island, Coffin Island, and Disappointment Island. It had been used to graze sheep and cattle, who were transported to the island by barge, or sometimes over the sand spit that connects the island to Antelope Island when the water level is low enough.

In 1861, the water level was high enough that access to the island was by boat. Baptiste was left on the island, which is sometimes reported as his having been exiled. However, it seems likely that it was meant to be a safekeeping measure until he could be brought to trial. When cattle herders visited the island three weeks later, they found no sign of Baptiste, except for evidence that he had attempted to build a raft: a dead cow whose hide had been tanned, and boards ripped from a small ranch house. No sign of Baptiste ever surfaced again, and his ultimate fate is still a mystery.

Fremont Island, the third largest in the Great Salt Lake, is privately owned and has sometimes been used as a private hunting preserve.

When pioneers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints first entered the Salt Lake Valley and began to colonize Utah and surrounding areas, the land was part of Mexico. However, following the Mexican-American War the territory, along with California and most of the Southwest, was ceded to the United States.

For seven years, Brigham Young, also prophet and head of the Church, was also the territorial governor. However, in 1858, amid inaccurate reports of the Saints' intent to rebel against the US government President James Buchanan sent troops to enforce obedience and government officials to replace those already in place. There was a crisis, lots of people moved temporarily to Utah County, and eventually a negotiated settlement was reached which led to the establishment of the Army at Camp Floyd in Fairfield and the installation of Alfred Cumming as the second territorial governor. Cumming served for four years, attempting to balance between the hard-line federal judges and the locals. After his term ended, he was replaced by John W. Dawson of Indiana in December 1861.

|

| John W. Dawson, Governor and Cad |

Dawson's time in Salt Lake City lasted less than three weeks. He reportedly made a pass at a widow. She responded by beating him with a fire shovel. Dawson fled the city on December 31, 1861, possibly to escape the irate relatives of the widow. However, some young men acting as vigilantes caught up to him at Mountain Dell, the first stage stop east of Salt Lake City. They beat him severely and looted his luggage. He returned to Indiana and later gained fame as the first biographer of Johnny Appleseed, his childhood friend. Dawson stands alone as the shortest-tenured governor in Utah history. Which is saying something, as there were several territorial governors during the Ulysses Grant presidency who lasted 3-4 months.

The men who assaulted Dawson were pursued by law enforcement. Of a reported seven assailants, four were arrested and three were killed by police officers while trying to escape.

And then the story gets stranger. But first, a digression into pioneer burial practices. When they first arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, the deceased were interred in what was called Block 49, near the original settlement. This early cemetery was rediscovered in the 1980s during development work and excavated by archaeologists from BYU. These early burials, owing to the poverty of the Saints, were often buried in simple shrouds fastened with brass pins, although coffins were also found.

Some residents, seeking a quieter and more scenic location for their loved ones to rest, began to inter the deceased on a foothill northeast of the city (the Sexton's House is at 4th Avenue and N Street). This was quickly normalized into an official cemetery owned by the city and an ordinance was passed to disallow burial in other locations.

So, Moroni Clawson had been one of the young men arrested for assault. He escaped from the penitentiary, but was shot by a Salt Lake City officer while fleeing. His family did not immediately claim the body, so a member of the police force, Henry Heath, paid for burial clothing out of his own pocket and Moroni was interred in the city cemetery.

A week later, Moroni's brother George exhumed the body to move it to the family plot. He was surprised to find, and Heath was surprised to hear, that there was no clothing at all. Heath began to investigate and hit upon a gravedigger, Jean Baptiste. Baptiste had lived in Salt Lake City with his wife for around three years. When officers visited his home, they found boxes of stolen shoes, clothing, and other goods taken from approximately 300 graves.

The reaction to the crime among the populace was intense. We should remember that the Saints had been driven from every previous place they had lived, leaving behind the graves of parents, siblings, spouses, and children. Not to mention the mostly unmarked graves left along the trail west. The idea of having a place for their dead to rest, where they could watch over them, was important.

A mob gathered outside the jail, threatening to lynch Jean Baptiste. The police department, hoping to keep him safe until trial, smuggled him out of the jail to Antelope Island. They quickly moved him to Fremont Island, which was more inaccessible.

|

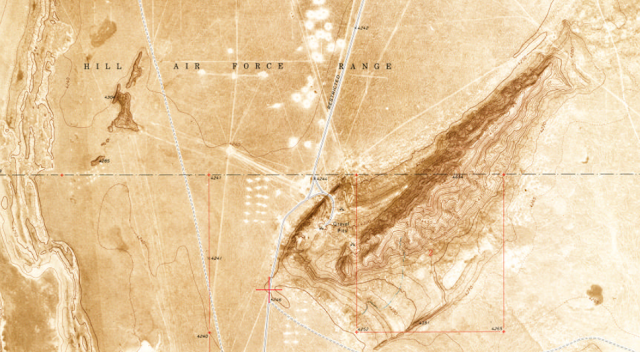

| Fremont Island in the center. The north end of Antelope Island is on the left. |

Fremont Island, named after explorer, military officer, and presidential candidate John C. Fremont, had been named by Captain Stansbury during his survey of the Great Salt Lake, although it had also been called Castle Island, Miller's Island, Coffin Island, and Disappointment Island. It had been used to graze sheep and cattle, who were transported to the island by barge, or sometimes over the sand spit that connects the island to Antelope Island when the water level is low enough.

|

| Free Soil, Free Men, and Fremont! |

In 1861, the water level was high enough that access to the island was by boat. Baptiste was left on the island, which is sometimes reported as his having been exiled. However, it seems likely that it was meant to be a safekeeping measure until he could be brought to trial. When cattle herders visited the island three weeks later, they found no sign of Baptiste, except for evidence that he had attempted to build a raft: a dead cow whose hide had been tanned, and boards ripped from a small ranch house. No sign of Baptiste ever surfaced again, and his ultimate fate is still a mystery.

Fremont Island, the third largest in the Great Salt Lake, is privately owned and has sometimes been used as a private hunting preserve.

|

| Fremont Island, from its highest point, Castle Rock. From Wikipedia. |

Comments

Post a Comment