Nine Days and Four and a Half Miles - Survival in the Lark Mine Cave-In

by Peter

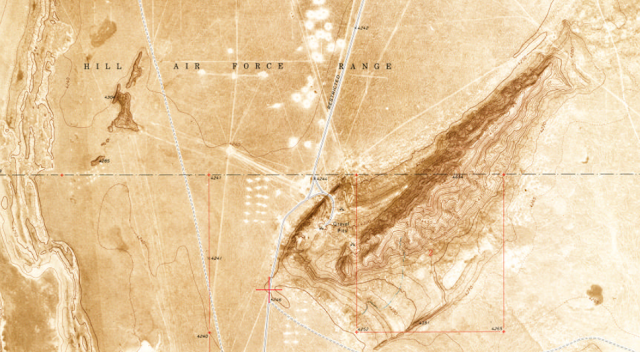

The waste rock piles of the Bingham Canyon Copper Mine dominate the western edge of the Salt Lake Valley. The history of Bingham Canyon and its supporting communities is fascinating in and of itself, but our story today focuses on the former town of Lark, located about three miles south of Copperton and on the eastern edge of the current mine.

The Bingham Canyon Mine in 2005. Photograph by Andrew Crouthamel. Used under Creative Commons License.Lark was officially founded in 1866, centered around claims that had been discovered by those prospecting the Oquirrh Mountains after the discovery of gold and silver in Bingham Canyon. Like many mines, the mines around Lark (including Dalton, Lark, Lead, and Antelope) ran into difficulties with flooding as they worked their way down into the ore bodies. Eventually a long tunnel (the Mascotte Tunnel) was cut from Bingham Canyon to Lark, allowing drainage of many mines and providing a direct connection between the two areas. Ore from Bingham Canyon was shipped through the tunnel for processing in Lark, while ore from the Lark mines was often shipped elsewhere.

Mining has always been a dangerous business. From collapses and explosions to poisonous gas and silicosis (lung disease from inhaling fine particles), thousands of miners have died from their work, including hundreds in Utah. One of my own ancestors was killed by gas in a mine near Alta in the 19th Century. However, our story takes place in the 20th.

By 1969, the workings of the mines had stretched miles into the earth and were primarily producing lead and zinc. On Saturday, March 1, 1969, William 'Buck' Jones and another miner found themselves in a riser, a narrow, uneven tunnel connecting two levels of the mine. The riser was some four and a half miles in from the entrance. The ceiling of the riser began to sag. Buck pushed the other miner out of the riser while attempting to shore up the ceiling. Soon, though, the riser had filled with muck.

Rescue crews from the mine immediately began to work to find Buck Jones, then 61 years old. Wary of causing additional collapses, they worked only with hand tools such as picks and shovels and shored up the tunnel with timbers as they progressed. The narrowness of the riser meant that only two or three could work on the face at one time. Hearing no response to their tapping and working, the rescuers feared the worst. As they contacted his wife Ethel, at home in Midvale with six of their eleven children, they also prepared her for the worst.

For five days the miners dug away at the collapse. Just after midnight on Wednesday, March 5th, Kenney Squires, one of four men working at the time, thought he heard a voice, but wasn't sure over the sound of the others working and the compressor they were using to provide themselves with fresh air. He stopped the work and they turned off the compressor. Faintly, still through several feet of rocks and debris, they heard, "When are you going to get me out of here?"

Buck Jones had been trapped by the slow settlement of the ceiling into a space measuring approximately 3 feet in diameter. Although air was able to filter through the collapsed material, he was trapped for five days with only his miner's lamp as company. After the rescuers heard his voice, they redoubled their efforts. An electric drill was brought in from Salt Lake City to drill a 2-inch conduit into his space so that water and vitamin and glucose packets could be passed through.

It took four and a half additional days for the rescuers to safely remove Buck from the mine. By all accounts, he was in remarkable shape, needing only a short stay at the hospital and a good shave. He continued working as a miner for another six years, retiring in 1975 and having survived at least three cave-ins and two or more industrial accidents during his long career. Buck passed away a little over 20 years after his brush with an early burial on October 21, 1989 in Basalt, Idaho.

Comments

Post a Comment