The Giant's Thumbprint - A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Davis County

by Peter

The Origin of the CCC in Utah

As Franklin D. Roosevelt became President of the United States in 1933, he recognized a serious need to combat the ravages of the Great Depression. With 2 million displaced people roaming the country, including 250,000 young people, and youth unemployment rates of 25% (with another 29% working part-time only), an entire generation was being scarred by economic despair (Salmond 1967: Chapter 1). At the same time, public land, particularly in the Midwest and West, was scarred by overexploitation, including heavy logging that had removed 7/8 of the original forests and subjected 1/6th of the land to severe erosion (Salmond 1967: Chapter 1).

Roosevelt saw an opportunity to address both needs and directed his staff to develop a program to employ as many as 500,000 young men on conservation projects in the nation’s forests and national parks. Congress approved an “Emergency Conservation Work” program in March 1933 with the goal of employing as many as 250,000 men that summer (Speakman 2006).

Men were invited to apply through their local relief agencies, who made the selections as to who would be enrolled in the program for 6-month periods. The Army took the men through a 2-week conditioning course and they were assigned to camps. Although efforts were originally made to keep enrollees close to home, the imbalance between population and public lands in the East and West resulted in many eastern men being sent to the West. Recruits earned $30 per month, of which $25 was automatically sent home to support their families (Speakman 2006). The CCC reached its peak in the summer of 1935 when it employed over 500,000 men (Baldridge 2019:101).

The first company in Utah was organized shortly after the program was authorized by Congress. The first enrollees were mustered in on May 5, 1933 at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City. On May 17th, 25 of these enrollees were organized into Company 940 (Spirit of ‘48 n.d.).

|

| CCC workers building a spillway east of Centerville. Photograph from the Utah Division of State History. |

The CCC in Davis County

The first CCC camp in Davis County was SE-201 (State Erosion). According to Baldridge, although this camp is often listed as located in Woods Cross, it was located in Bountiful, first at Mueller Park and then at the future site of Camp F-48 (2019:157). This camp, staffed by Company 232 from New Jersey and New York, operated only during the first 6-month enrollment period in 1933.

As the CCC expanded in Utah, two major camps were eventually established in Davis County along with several smaller camps, often called stake or stub camps. The two major camps were SP-2 in Woods Cross, occupied by Company 536 and F-48 in Bountiful, occupied by Company 940. A transient relief camp was also established in Farmington, which provided short-term housing, food, and employment for up to two weeks for men passing through the area.

|

| Bountiful Stub Camp, Summer 1934. Unknown Location. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

Company 536 - Camp SP-2

The men of Company 536 were drawn from the Fifth Corps area, primarily Ohio and Kentucky, with a few men from West Virginia. After stops in California, Wyoming, and Nevada, the company relocated to Woods Cross in August 1935 (Ukenova News, n.d.). The camp, SP-2 was under the direction of the State Parks division and was established to construct a large dike to create the Farmington Bay Watefowl Refuge on the eastern Great Salt Lake. The camp was located on the border between Bountiful and Woods Cross. Based on an aerial photograph from 1937, it was likely located at approximately 1375 South 500 West (US-89).

|

| Camp SP-2 at Farmington Bay. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

The project was intended to create breeding areas for waterfowl and to improve duck hunting in the area by impounding some 3,600 acres of fresh water in a shallow lake. By August 1936, the company had constructed 5.5 miles of dike along with a number of access roads (Derks 1936). By August 1937, the length of dikes constructed had reached 8.8 miles and it was asserted that one more year of improvements was required (Doxey 1937). The work was finally completed in July 1940 having used 80,000 cubic yards of gravel and 900,000 cubic yards of dirt at a cost of $400,000 (Salt Lake Telegram 1940). The camp was disbanded that same year.

|

| Another View of Camp SP-2. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

|

| Company 536, August 5, 1937. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

|

| Ora Howell from Camp SP-2 at Farmington Bay. Photograph from Utah Division of State History |

Company 940 - Camps SR-205, F-48, and F-49

After the formation of Company 940 in May 1933, the company was sent to American Fork Canyon for the summer. However, as winter began to make work there impracticable the company was shifted to a disused cannery in Woods Cross. This was likely the cannery of the Woods Cross Canning Company, located at approximately 600 South 800 West. It was given the designation SE-205 (for State Erosion). The following summer, a stub camp was established somewhere in the hills above Bountiful, although the location of this camp is uncertain. Company 940, initially under the direction of the state erosion control program, began working on projects meant to mitigate flooding from the canyons in eastern Davis County after heavy rainfall.

|

| Company 940, likely in 1934 or 1935. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

In October 1935, the company moved to Camp F-48, which had been constructed that summer in Bountiful. The camp was located at 1018 East 250 North, now the site of Holbrook Elementary School. This move also changed the oversight of the company from the state to the US Forest Service. In 1937, the company established a stub camp called F-49 at a location called Red Flats, up Farmington Canyon. Although the location of this camp is uncertain, it was likely in the area now known as Farmington Flats, near Bountiful Peak. This camp was used during the summer as the men worked on projects high in the Wasatch Mountains. As snow limited their ability to work there each winter, they would shift back down to Bountiful.

|

| Camp F-48, Bountiful. Photograph from Weber State University, Stewart Library. |

Two additional camps are mentioned in the camp newspaper. These were called horse camps and the newspaper discussed the camp being shifted from Farmington Canyon to Lime Canyon. These may have been temporary camps to care for the horses being used on specific projects. Their exact location is uncertain.

The work conducted by Company 940 generally fell into two categories: contour trenching and flood control structures. Both were techniques used to control runoff and flooding. This was generally considered to have resulted from overgrazing in the mountains, although severe flooding had been noted historically and geologically (Baldridge 2019:159-160)

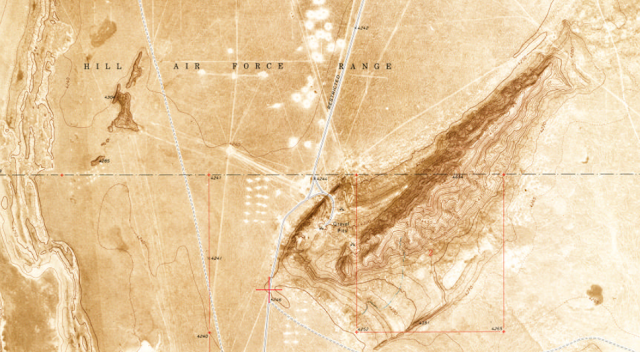

Contour trenching involved the construction of a series of parallel trenches along bare slopes on hills and in canyons. A trench was dug and the spoil from the trench stacked to the outside to create an excavated terrace. Most were dug by hand or with the aid of a horse-drawn scraper. Although terraces have long been used to control runoff and allow farming of steep slopes, the addition of trenches in the terraces increased the capture of runoff from 25% to 75%. After three years of work, the men from the Bountiful camp had constructed 700 miles of trenches, equal to the distance from Bountiful to Los Angeles. This number had increased to over 1,000 miles before they were finished. (Baldridge 2019:161-164). More than 750 acres of trenches are currently visible on aerial photographs of Davis County, as well as small areas of Salt Lake and Morgan Counties that were constructed by the Bountiful Camp, although additional areas may have been trenched that are now obscured by vegetation.

I think the contour trenches, when viewed from above, look like a giant's thumbprint on the hills. These trenches are near the Bonneville Shoreline Preserve on the border between Salt Lake and Davis Counties.

|

| CCC contour trenches at Lime Canyon in North Salt Lake. View to the southeast. Photograph by the author. |

|

| Detail of contour trench at Lime Canyon in North Salt Lake. Photograph by the author. |

According to the F-48 Camp History, “At the mouths of most of the canyons between Salt Lake and Weber Canyon, flood dams, dykes, spill ways and water guides have been placed to protect farms and other property from flood waters” (Spirit of ‘48, n.d.). A 1935 accounting of the work of the company lists work in South Weber, Walton, Baer, Webb, Farmington, Steed, Davis, and Parrish Canyons. Structures are also known to have been built at Farmington Canyon, Shepard Creek, Corbett Creek, Adams Canyon, and on an unnamed drainage east of Centerville.

These structures were built of earth and native stone and included mortared and unmortared walls, dams, dikes, and spillways. The stonework of the CCC is generally quite distinctive and instantly recognizable. The construction of the contour trenches and other water control features effectively ended the destructive flooding of eastern Davis County.

The men of Camp F-48 also constructed the road from Bountiful to Mueller Park, improvements in Mueller Park, and Skyline Drive in Farmington Canyon and the Wasatch Mountains (Baldridge 2019:125).

|

| A flood control wall near Adams Canyon. Photograph by the author. |

|

| Detail of the stonework in the Adams Canyon wall. Photograph by the author. |

|

| Detail of stonework in a different CCC flood control structure in South Weber. Photograph by the author. |

|

| The men of Camp SE-205, Company 940 signed their work at the South Weber structure, dating its construction: 1935. |

Life in the CCC

Camps were constructed in areas where projects had been identified by the US Forest Service, National Park Service, and other federal or state agencies. Work was varied and included erosion control, water control, grazing improvement, tree planting, and road and trail building. The camps consisted of military-style barracks, mess halls, administration buildings, and educational buildings. Camps were overseen by reserve military officers and also had a civilian superintendant assigned by the sponsoring agency (such as the Forest Service). Locally Employed Men (LEMs) were also engaged by the camps. The LEMs were older and generally married and provided additional supervisors who were skilled in the techniques needed to construct assigned projects. Many of the men ate better than they ever had before, gaining an average of 12 pounds over the first two months (Speakman 2006). Baldridge describes a standard supper at Camp F-48 as consisting of, “chicken, lettuce and tomato salad, creamed peas, mashed potatoes, ice cream, and lemonade, while salmon, salad, prunes, and iced tea formed the nucleus for dinner” (2019:265).

In addition to providing food, lodging, and employment, the camps also provided recreational and educational opportunities. Most camps organized sports teams that competed against other camps and teams from local communities. Basketball and baseball teams are especially noted, but camps also often housed boxing and billiards equipment (Speakman 2006). Educational classes were offered in the evenings after the completion of the day’s work under the direction of a camp Educational Advisor. Subjects offered included subjects such as math and English, as well as vocational training in automobile repair, carpentry, and other subjects. By 1938, 603 different subjects were taught in the various camps (Speakman 2006).

|

| Interior of barracks in a camp in Montana. Photograph from the Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. |

The camps were under the direction of an active-duty or reserve military officer; usually a captain, but sometimes a first lieutenant. He was assisted by one or two junior officers. A medical officer was also assigned, who sometimes served more than one camp (Salmond 1967: Chapter 4). Camps also had a First Sergeant and a Supply Sergeant drawn from the ranks of the enrollees. Along with the manual labor, some enrollees were assigned to assist in the infirmary, commissary, kitchen, and other areas of the camp. The work undertaken by the men was under the direction of a civilian superintendent who was employed by the sponsoring agency (Spirit of ‘48 n.d.).

With enlistments lasting six months, the men in any given company were pretty constantly in flux. Camp newspapers report those leaving the company regularly, many of them having obtained regular employment in industry, in the military, or in the regular civil service with the assistance of their CCC training. Commanding officers also changed regularly, with Company 940 having four commanders in its first four years. Company 940 was disbanded in October 1940 and its men sent to other CCC units. Camp F-48 was then occupied for a limited amount of time by Company 1741, primarily from Arkansas, before being closed permanently.

|

| Mess Hall in an unidentified camp. Photograph from the Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. |

|

| Playing football in an unidentified camp. Photograph from the Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. |

|

| Kitchen crew in an unidentified camp. Photograph from the Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. |

|

| Leaving for home from California. Photograph from the Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. |

1933-1942. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Comments

Post a Comment